'

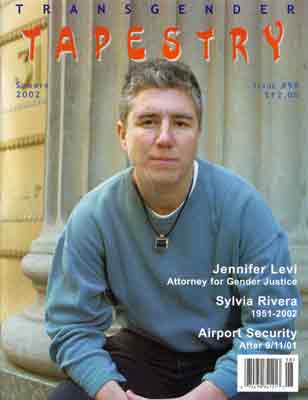

Jennifer Levi: Attorney for Gender Justice (TT098.28)

by Gordene O. MacKenzie

and Nancy R. Nangeroni

(from Tapestry 098)

In the second half of the last decade, the board of directors the Boston-based Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders (GLAD) decided to look closely at the emerging arena of gender and transgenderism, in hopes of incorporating some of the perspectives emerging from that movement into their work. As a group of attorneys litigating key cases in hopes of setting far-reaching precedents in defense of LGBT persons, the GLAD board made it their mission to advocate on behalf of those who had been denied justice because of their gender.

Four years ago, they offered a job to a trans-identified attorney from Chicago who had been helping transpeople with legal concerns in her spare time. That attorney was Jennifer Levi. Since that time, Jennifer has been involved in?and won?a number of high-visibility court cases in the New England area, establishing far-reaching precedents on matters dear to the transgender heart. She was the primary drafter of Rhode Island?s transgender-inclusive non-discrimination law. She has been instrumental in winning favorable rulings for transpeople in employment, health care, lending, public accommodations, and education. Her arguments produced a legal victory in the Brockton, MA case where a biologically male transgendered student won the right to attend school wearing ?girl?s? clothing. She is working to ensure transpeople are included under federal sex discrimination law. We spoke with Jennifer about gender case law, and about her own gender identity and beliefs.NRN: How did you come to be a committed advocate for gender diversity?

JL: It started a long time ago. I came to some kind of consciousness about my own identity after reading Leslie Feinberg?s Stone Butch Blues. I had come out as a lesbian before then. Growing up, I had always been seen as a boy, and over a period of time I could see it brought shame and embarrassment to others around me, including even my family, which has always been supportive of me. I could tell it wasn?t a good thing for me to be perceived as a boy when in public, even though no one ever directly told me my gender expression or the way I looked was a bad thing. When I came out as a lesbian in college, I felt easier about my gender expression.

Reading Stone Butch Blues, though, made me think about the possibility that my issue was related more closely to gender identity than sexual orientation. I?d never thought about gender expression as being an identity?as even being significant, for that matter. When I came out as lesbian, I met and found a community I felt comfortable in. But after reading Stone Butch Blues, I realized my experience of difference had been related much more to my gender expression than to my sexual orientation?although that remains significant, just not in the same ways.

I?ve always thought I share as much gender identity and probably gender expression with my brother as with my sister. When people would look at me and refer to me as male, I never thought they were wrong. I thought what they were saying was that I wasn?t gendered female, and I always thought that was true. I could look at my sister and say, ?We don?t share the same gender.? And so, having a transgender identity has been so welcoming for me, and appreciated.

GOM: Maybe that?s because lesbian feminism opened up a space that created community on some level, and then with gender another level opened up.

JL: Coming out as lesbian put relational pieces into place for me, but didn?t put self or identity pieces into place. So I decided I would read everything I could about trans anything. Around that time I was teaching and had a bit of a travel and conference money. I thought, ?Well, I?ll go do transgender legal something or other.? I found this conference in Houston, the International Conference on Transgender Law and Employment Policy. I went, and it was the most incredible experience, because for the first time, and I steal this line from my lover, ?I felt so ordinary.? That was a transformative experience, one that motivated me to become increasingly involved in the legal struggle.

GOM: What led you to law, and what kind of law did you focus on, and how did you get to GLAD?

JL: I worked in the tech industry in the late 80s. As I advanced in that career, the work became more technical and less interesting. I was also increasingly involved in gay and lesbian politics and activism, so I thought that if I went to law school, it would be a way to do something practical in advancement of gay and lesbian civil rights. When I graduated, it was hard to get jobs in the public interest, so I worked in a large law firm, where I was unhappy for several years. I taught law in Chicago for a couple of years. That?s when I started doing transgender legal work as a cooperating attorney with Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund. They were happy to have somebody to whom they could refer those cases. Then I got the job at GLAD and moved across the country.

NRN: What was it like in those early days of working on transgender law?

JL: It was hard. There wasn?t a lot that you could do for people. Some of the questions were basic ones about document changes. There was more that you could do for people who, for example, had been unfairly denied name changes. When custody cases came up, we tried to get people to psychiatrists or psychologists who would give a favorable report to a court.

GOM: Was that hard, back then?

JL: Then and now. It?s really hard around the custody issues, partly because if you muster up your national resources you can pull together a good qualified team of experts, but for any particular state or community there are not a lot of people who have expertise in the area.

NRN: One of your early cases involved a transsexual woman who had breast implants, and then had trouble with them and needed reconstruction.

MJL: She had been denied coverage by Medicaid for a breast reconstruction, relying on the Medicaid exclusion for sex reassignment surgery and treatment and procedures relating to it. The state said they?d pay for the removal, but not for the reconstruction. We got that reversed in an important decision that acknowledged that if somebody transitioned 25 years ago, her need for breast reconstruction wasn?t in the advancement of or for the purpose of transitioning.

NRN: What kinds of cases do you typically handle?

JL: A broad range. I?m committed to ensuring that disability laws extend to transgendered people who face discrimination either because of a perception that they have a serious health condition or because they do have a serious health condition. Although I don?t want to overstate this, I acknowledge that there?s some disagreement both within and outside the community about whether to pursue disability-based protections for transgendered people, for fear of perpetuating the stigma we already face. I strongly believe that these objections are based on a misperception of disability discrimination law. There?s a real problem with stigma associated with disability, but the answer isn?t that people with health conditions shouldn?t rely on the law that?s intended to protect them. The answer is that we should be fighting that stigma.

GOM: In the late 80s or early 90s, an amendment was tacked onto the Americans With Disabilities Act, excluding gender and sex minorities and lumping them with pedophiles and sex offenders.

JL: Federal law explicitly excludes transgendered and transsexual people from the ADA. It?s not based on any principled exclusion that looks at whether somebody can meet the definition of being disabled. It?s based on a stigma that associates transgendered people with criminals.

GOM: But now you argue from a different vantage point, that it?s a form of disability if it prevents a transperson from being able to work or keep their job.

JL: Most states have a definition of disability that says a person is covered by the law if they can demonstrate they have a serious health condition and that they are substantially limited in a major life activity because of that condition. For many transgendered people, their gender identity is related to a significant health condition. For purposes of the law, whether you characterize it as a mental health or physiological condition doesn?t matter. Some people characterize their own transgender identity or condition as being endocrinological or neurophysical. Some people identify with having gender dysphoria, and for them it?s a mental health condition. The basic requirement of a serious health condition is met for many people; if they can?t get hormones, treatment and therapy, they?re substantially limited in every major life activity. They may indeed be suicidal, they may be profoundly depressed, and it may inhibit the ways in which they interact with other people. That?s the legal definition of a person with disability. So if someone is discriminated against because they have that disability, if, for instance, somebody comes out as being transsexual in the workplace and they?re fired because of that particular health condition, they should have recourse through the disability discrimination laws.

NRN: That is, sex discrimination and disability discrimination.

JL: Exactly. What unfortunately has happened is that because of the stigma related to disability, a lot of people, even within the transgender community, have sought to exclude us from the protections of those laws. For example, in the case involving the transgendered student in Brockton . . .

NRN: This was the student born male who insisted on wearing a dress to school.

JL: Right, and everybody was fine with it except for the administrators, who said, ?You have to come to school looking like a boy.? We brought claims of both sex discrimination and disability discrimination, and we obtained favorable decisions on both. As the court explained it, one reason why it was disability discrimination was because asking this student to change her gender identity would be like asking her to change any other physical condition. For example, a school could not require a student who was 5?8? to attend school only if she became 5?6?. Because gender identity is not something a person can change, the judge ruled the school needed to accommodate the student?s disability. It?s unfortunate language, and I think it makes people uncomfortable, but there?s no principled reason to exclude people from the protections of the law just because of the stigma.

GOM: I remember when sex discrimination wasn?t being considered for transsexuals. It seems like change came out of an unexpected direction?the Hopkins v Price-Waterhouse decision that a woman being discriminated against because she wasn?t feminine enough and didn?t wear makeup. All of a sudden, we had this gender opening so we could start looking at possibilities for trans-inclusion.

JL: Yes though most of the early cases in which we have had success are not the classic cases in which claims on behalf of transsexual people were denied, but rather have involved gender non-conforming people who may or may not even identify as transgendered. But hopefully, we have laid a foundation for bringing those other, arguably more difficult claims.

GOM: In the late 80s and early 90s it seemed both disability and sex discrimination were dead as arguments.

JL: Yes, though that?s certainly not true now. You now have two state human rights commissions which have interpreted state sex discrimination laws to include transgendered people?Connecticut and Massachusetts.

NRN: When you talked to the medical professionals at the Harry Benjamin Association, you encouraged them to help the transgender community in the area of family law?

JL: One of the most important things the medical professional community can do is to explain that transgendered parents are good parents and that the best thing that you can do in terms of providing a good home for children is to strengthen their relationship with their parents. In the gay and lesbian political arena, it took some time to build a broad-based consensus that gay parents are good parents. It?s a critical role medical professionals can play, to explain to people that there?s no correlation between negative outcomes for children and having a transgendered parent. The other pieces that are important for medical professionals are to assist courts in understanding that somebody?s sex is not necessarily defined by either their genitals or by one particular factor, for instance chromosomes.

NRN: What about moving out of a strict binary interpretation of sex?

JL: I actually like gender. I don?t necessarily adopt the idea of binary definitions of gender, although I am attracted to that as well. It?s something I understand and that fits into my world. However, I would say that there should be no legal significance to either someone?s gender identity or their physiology. The only circumstances I can think of where a person?s sex matters from a legal perspective are one in which the intent is to discriminate against gay and lesbian people. The reason we need to know somebody?s sex when they get married is to insure that same-sex couples can?t marry. I don?t know why we have to put sex designations on driver?s licenses. You see my picture; that?s what you need.

NRN: We don?t keep religion on driver?s licenses because we don?t want to discriminate on the basis of religion. If we don?t want to discriminate on the basis of sex...

JL: Right. But my identity as a feminist, my identity as a lesbian, and even whatever sort of relics I have with my identity as a woman are all integral pieces of who I am, so I?m not that interested in breaking down gender. I like gender. It defines me. If I could give an analogy, I think race and religion are important identities for people. They create community, and, admittedly, create division and wars and all that stuff, but I hope most people at this point would agree they should be legally irrelevant categories and that what people want to do with them beyond that is up to them. My real goal is to work towards the legal irrelevance of gender.

GOM: What about litigation about people born as intersexuals? Or intersexual arguments used in gender case law?

JL: The arguments get used, and the fact that there are intersexual people can help raise awareness that there really isn?t a clear and true dichotomy of sex. But I don?t think it necessarily drives home the point, because then people think, ?Well, there are men and women, and there are intersexuals.? I think there?s more work to be done, both in terms of identifying and understanding the legal concerns of intersexual people and figuring out appropriate ways to raise awareness of intersexual people with dignity for that community and others.

It?s been said to me?and it makes sense?that the real concerns of the intersexual community are around sex designation at birth. We hear about the kind of rank discrimination in employment in intersexuality less frequently than in transsexualism.

GOM: A concern of intersexed activists is surgery without permission.

JL: Yeah. The hardest thing is of course that there?s no infant intersexual community to stick up for itself. The support of intersexed adults, though, has been critical in advancing awareness of the issues.

GOM: What sorts of groundwork do we need to lay for the next generations, in terms of gender and law. What kind of questions do we need to ask?

JL: That?s a very hard question. As a lawyer, I react to problems and don?t do as much forward thinking and planning. Maybe the next questions will be about what gender is and how we would want future society to be structured.

GOM: These days in the media, we see more manly men and pinup women, as gender roles become more divided. As the war drums beat, do you see a backlash or a scapegoating around gender or people that are differently gendered?

JL: More than anything, I see strides in education. When I was in Rhode Island at the hearings to add gender identity and expression to the non-discrimination law, the legislators didn?t have a clue about what we meant when we talked about transgender or gender stereotyping or a continuum of gender expression. People, though, had a sense that it was a bad thing to fire someone for being transsexual. That?s a quantum leap. Now, it?s far from what I think a lot of us are talking about in terms of broader understandings of gender, but I don?t think it?s so much a backlash. I think there?s more education, more awareness, more understanding. It?s incredibly limited and narrow at the moment and needs to be expanded upon.

To start where people have a bit of understanding is important, because though many of us have thought about these issues for our entire lives, some people don?t think about them at all. To tie it to my personal experience, my family is tremendously supportive. They always have been. I think it was actually a surprise to them that it made me more uncomfortable to have them correct people about my gender than to let the references go. I think they felt they were sticking up for me because they wanted me to be able to look however I wanted to look and not have to be uncomfortable. They didn?t understand, and I couldn?t understand then, either. It took a while to explain to them why I?m comfortable being referred to in public as he, and why that confirms and affirms my gender identity rather than undermines it.

One of the reasons we?ve been able to make as many strides as we have in the gay and lesbian community is because, increasingly, few people can say ?I don?t know a gay or lesbian person.? I think it?s the responsibility of those of us in the transgender community to be out, to be vocal, to be visible, so that hopefully there will be fewer people who can say ?I?ve never met anyone who is transgendered.?

NRN: What is Oncale vs Sundowner?

JL: Oncale vs. Sundowner was a same-sex sex harassment case that up to the United States Supreme Court. It was a critical case because the court acknowledged that when it passed the sex discrimination laws, the legislature had not explicitly intended, to address same-sex sexual harassment. The court said that if the language of the statute is clear, it would apply in those circumstances despite the fact that nobody had anticipated that application.

NRN: That?s an important legal principle, because it says the principle is important, not the practice that was known at that time.

JL: Exactly. And it?s the reason why the early cases of discrimination against the transgendered in employment were thrown out with the courts saying they didn?t involve sex discrimination are just ludicrous. If someone is a fine employee when they?re male, and then transitions and gets fired because they came a woman, there?s no principled way to argue that the adverse employment decision is not because of the employee?s sex. But what those old cases said was that the legislature never could have intended for the law to extend to a transsexual person.

What the principle from Oncale says is that?s not the way to interpret the statute. The way to interpret the statute is according to what it says, not solely by what the legislature had in mind when it was written. The fact that nobody was thinking about transgendered people doesn?t mean transgendered people are excluded from its protections any more than a man who is harassed by another man in the workplace.

GOM: In one of your articles you said the things that alarmed people the most were cases involving bathrooms and the fear concerning men in dresses in the workplace.

JL: They?re hard issues. In terms of the bathroom issue, I think there must be basic education about who transgendered people are, addressing the underlying myths that generate anxiety. For example, transgendered women are not men who are masquerading as women in order to harass women, or to be voyeurs. I think FTMs can be instrumental in that educational work, because nobody wants to share a women?s restroom with an FTM, appropriately so.

I think that educational piece is going to happen at a second stage, once we?ve established some basic protections, as we have in Massachusetts and Connecticut and now Rhode Island. To establish those basic protections, you must be able to integrate transgendered people into the workplace. You need to provide safe environments for people to go to the bathroom. You can get to that second level of education only when you?ve set that foundation, the basic principle of non-discrimination.

In terms of men in dresses in the workplace, I think some of that misperception stems from some basic misunderstandings about transgendered people, the view that we?re either wanting to be disruptive or are troublemakers. We need to address those basic issues. Frankly, some of it is also feminist education, and working even harder to ensure men have a broader range of gender expression available to them. With education, even if people have misunderstandings, they?ll be less fearful of working with them.

I think that difference makes people uncomfortable, and as more people become more visible, come out, and talk about their own experiences of gender, the differences in gender and gender expression and gender identity become less threatening to everybody. It?s one of my hopes and aspirations that people will feel more comfortable talking about that, from whatever their experience is. Whether it?s someone who?s transsexual and passing, or a part-time crossdressing person, or someone who?s genderqueer, or somebody who doesn?t quite identify with all of the characteristics of being male or female, that adds to the general understanding people have about transgendered people, and makes it all less threatening to other people. That?s how we see change over time.

GOM: Tell us about GLAD?s role in all of this.

JL: GLAD has been one of the forerunners in doing this work, with a clear commitment to what is described in our mission as the ending of discrimination based on gender identity and gender expression. I appreciate the support we?ve gotten from our board.

There was never any real question about the importance of doing this work. When I came to GLAD, people wanted to understand about transgenderism. So my coming there, and bringing this passion to the work, just moved us on this path.

NRN: They really understood that gender is at the root of all of it.

JL: But the nice thing is I had the sense that it didn?t have to be that gender is at the root of sexual orientation discrimination in order to do the work. It?s just the right thing to do.

NRN: Do you want people to contact you if they have a case?

JL: Absolutely. One of the things we haven?t brought is a claim on behalf of a transsexual person who was fired after they transitioned, because they transitioned. We?ve laid the groundwork to bring that kind of claim, and, obviously, it?s important to go that next step. I?m also interested in challenging exclusions from coverage for Medicaid, particularly in Vermont and Connecticut. Some of that has to do with the case law there, where we can push things. I don?t always know the best time to bring cases, but I?m always deeply concerned when somebody?s challenging a parental relationship because somebody is transgendered, or challenging a marriage, or is denied the ability to change either the birth certificate or their name or documentation.

GOM: What do you do for fun, Jennifer?

JL: This is fun! Well, the funny thing is, when I wasn?t doing this work, when I was working my eight to eight or whatever, this is what I was doing evenings and weekends. It?s often still what I do on my evenings and weekends. It?s a great position to be in. For now, I wouldn?t trade it.

Nancy Nangeroni and Gordene MacKenzie have interviewed Jennifer Levi several times on GenderTalk radio. You can listen to those interviews, with much more discussion of recent gender issue court cases, at www.gendertalk.com.

Gordene is co-host and producer of GenderTalk radio. A transgender rights activist and educator since the mid 1980s, she is the author of Transgender Nation and director of the Women?s Studies program at Merrimack College in the Boston area.

Nancy is founder, co-host, and producer of GenderTalk radio. She is a writer and activist on transgender issues. She has been a transactivist and educator since the early 1990s.

Nancy and Gordene live together in a little house in the woods of North Reading, Massachusetts.

t